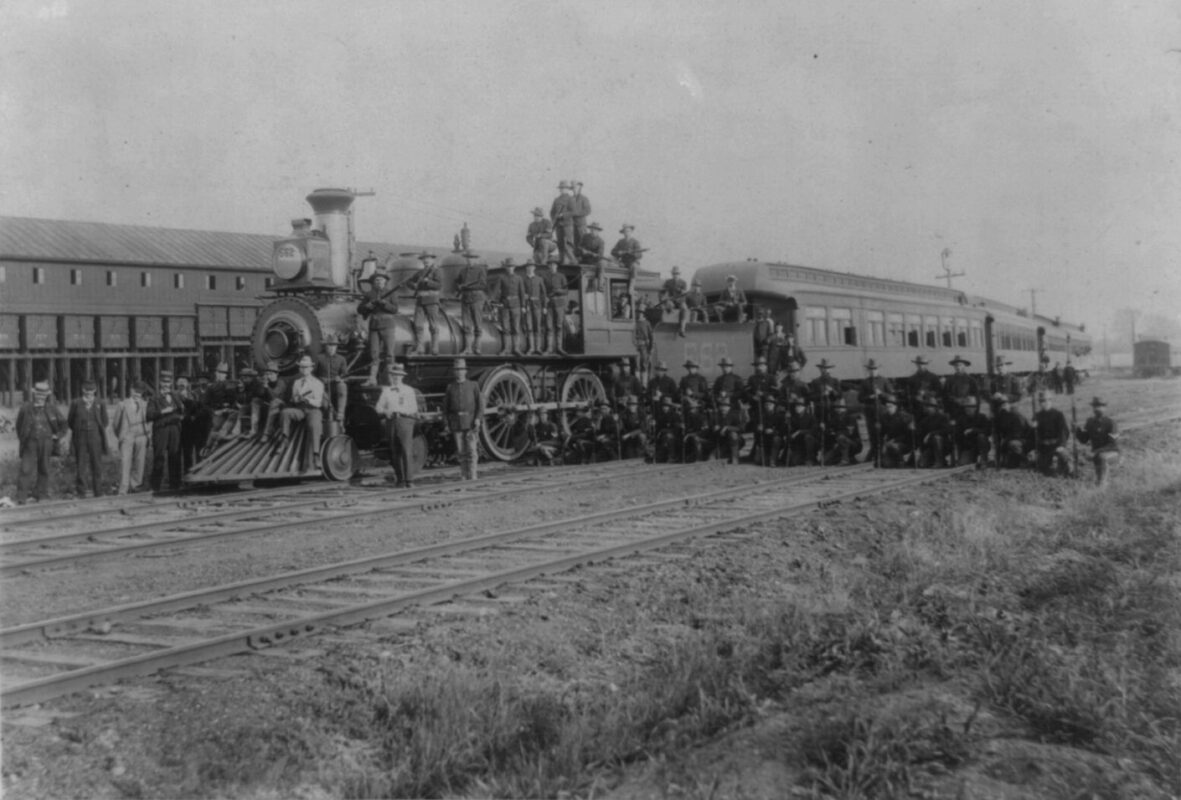

The image above (from the collection of the Library of Congress) shows a special patrolling train in Blue Island during the great railroad strike of 1894. Company C of the 15th U.S. Infantry (also in the picture) arrived in Blue Island during the morning hours of July 4th to quell the actions of railroad workers, led by American Railway Union President and political activist Eugene Debs, and those sympathetic to their cause, setting up camp north of Vermont Street close to the Rock Island railyard.

The strike began in nearby Pullman in May of 1894, where workers wages had been cut by Pullman Palace Car Company owner George Pullman, with no relief on rent in the company-owned town. After the concerns of the workers were ignored, they walked off the job, joined a month later by the rest of the country, as the American Railway Union voted to support the strikers by refusing to handle trains containing Pullman cars.

In Blue Island, those trains were detained in the Rock Island yard, with local hotels and restaurants refusing to serve passengers. Workers from other industries joined railroad employees as well, with local brick workers rallying to the cause. Some accounts attribute the more violent and riotous actions — toppling cars and jeering strikebreakers — to the brick workers, while railroaders remained disciplined.

But on June 30, two Rock Island railroad workers derailed a slow moving locomotive attached to a U.S. Mail train to block the line just south of the Vermont Street station, while others set fire to several nearby buildings. As a result of these actions, and as strikers grew violent in other parts of the country, President Grover Cleveland ordered troops to Blue Island from Fort Sheridan – now a neighborhood in the North Shore communities of Highland Park, Highwood, and Lake Forest. The occupation was successful in calming the situation in Blue Island after their arrival on Independence Day, but the same can’t be said for the strikers in Pullman & Chicago…

As troops neared the railyards on July 4, strikers erected barricades and overturned railcars to keep the them from entering. On July 6, rioters destroyed hundreds of cars in the South Chicago Panhandle yards, and national guardsmen fired into a mob after being assaulted on July 7, killing between 4 and 30 people and wounding many others.

In the days following the climax of violence and unrest, troops finally gained the upper hand. As the strike was called off and order was restored, there wasn’t much public sympathy left for the workers and their leader, Eugene Debs, following the 2 months of violence and uncertainty that gripped much of the country. Many of the striking workers were never re-hired, some of the leaders of the strike were jailed, and the public’s perception of organized labor suffered a major blow.

Though the labor movement would eventually gain steam again, Debs and his cohorts were jailed, put on trial, and eventually handed a sentence of 6 months in prison. While in jail, Debs began his journey from labor activism to socialism.